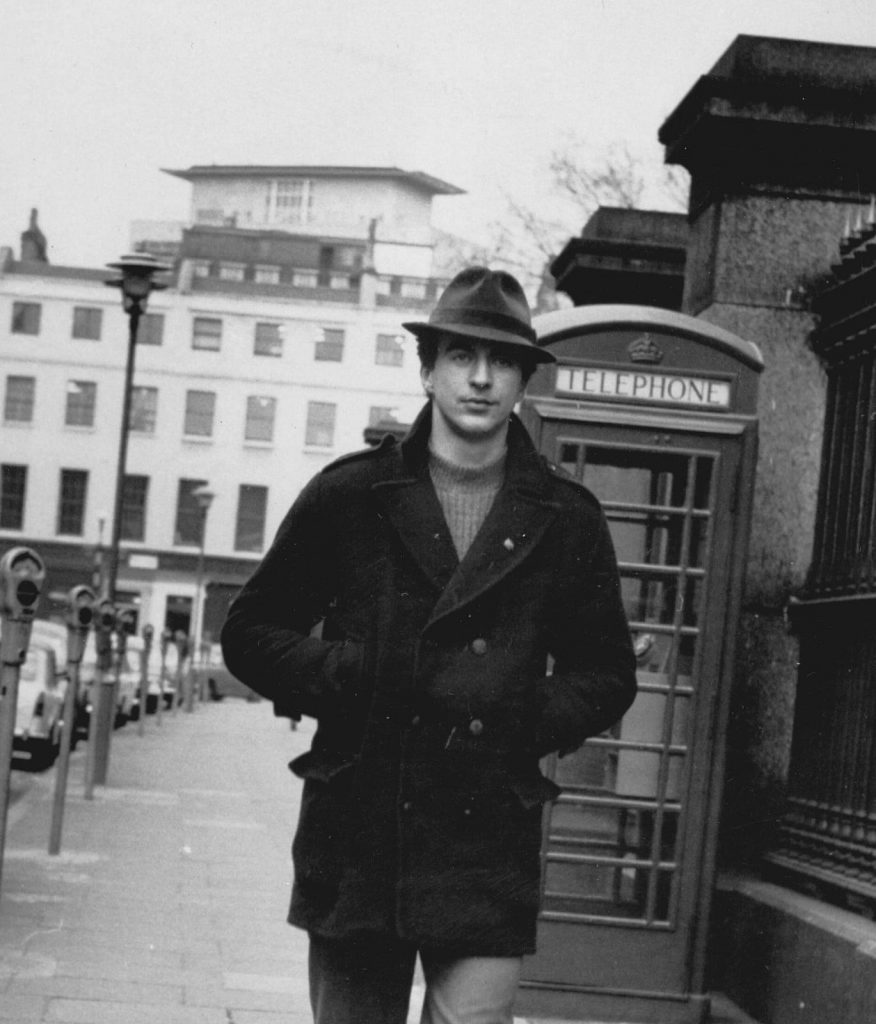

Stuart Christie, 10 July 1946-15 August 2020.

The death of Stuart Christie on 15 August 2020 has already led to an outpour of touching tributes and obituaries. With his untimely departure, the international anarchist movement has lost one of its most committed and dedicated activists. Indeed, the ‘measure of the man’ has been encapsulated by how many of us, from brief, often remote encounters, felt in some way attached to him by the warmth, intensity and generosity of his character. Stuart was an anarchist of the highest calibre; iron-willed, yet self-critical, fiercely independent in mind, but always motivated by a collective and egalitarian vision of social change.

My own personal correspondence with Stuart began during the final year of my degree in 2015. It was during this time when I wrote to Stuart with (in hindsight) poorly formulated questions for my dissertation, catchily titled ‘The Angry Brigade: Student Radicals, ‘The Society of the Spectacle’ and Media Representations of ‘Red Terror’, 1968-1972’). I half-expected Stuart to direct me to his collection of memoirs, or snub me as an ‘academic chancer’, rather than respond to each question in kind. But to my surprise he took the time to share his present-day thoughts on every detail of my enquiry. After my initial haphazard encounter, Stuart and I would correspond with one another for the next five years regarding new publications, archival exchanges, elusive primary sources, Spanish anarchists, and experiences in prison.

Indeed, in a more personal sense, Stuart’s death represents the loss of an irreplaceable guide and mentor. Historians constantly mull over the partiality of the ‘narrator-as-witness’. Rarer perhaps are those occasions when we reflect on how a narrator informs and motivates our own retelling of the past. I encountered Stuart’s memoirs when I was twenty years old. At this time I was already jaded by the petty intrigues of ‘radical’ student politics, riddled with class-born anxiety, and all too accepting of a precarious future. With Stuart, I was confronted with a person who, from an early age, was both assured of his own place in history, while also willing to take a leap into the unknown.

This ‘unknown’ was the Iberian anarchist movement in Franco’s Spain. As an undergrad History student in 2015, this territory was unfamiliar to me too. Yet three years after I became personally acquainted with Stuart, I would end up undertaking a PhD on the topic. Unlike more conventional trajectories, my fascination with Spain was not stoked by Orwell’s ‘Homage to Catalonia’, or Ken Loach’s ‘Land and Freedom’, but the unlikely and extraordinary tale ‘of a west of Scotland “baby boomer”’.

Stuart had spent most of his teenage years with his mother and Grandparents in Blantyre, a small isolated pit town, located to the West of Glasgow. Familial ties crossed with class politics in Stuart’s political formation. Along with the influence of his grandmother, the values of whom, Stuart later recalled, ‘married almost exactly with that of libertarian socialism and anarchism’, Blantyre was home in the 1950s to a confident working class. Centred around the NUM and the local Miners Welfare Institute, politics in the local area was synonymous with the Labour Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain. At the age of sixteen, as an apprentice working for a dental laboratory in Glasgow, Stuart had become politically active in the Young Socialists (the youth section of the Labour party). But it wasn’t long before Stuart became disillusioned with the procedural nature of Party life. Once exposed to ‘the machinations and power struggles within the Glasgow Labour Party’, Stuart’s idealistic and reflexive attachment to Party socialism was crushed by its culture of ‘office-grabbing’, ‘local political power plays’ and ‘contending sectarian power agendas’.

After exiting the Party, Stuart became involved in the Glasgow Federation of Anarchists and the anti-nuclear Committee of 100. A split from the ‘celebrity-and-politician dominated’ CND, the Committee of 100 mobilised against nuclear armament and militarism with direct action. Yet Stuart was drawn to questions bigger than those immediately posed by single issue campaigns. If war, imperialism, and violence came with the territory of the modern State, then perhaps it was the State that was the problem. As Stuart recalled in an interview in 2004, ‘I began to see a lot more clearly that it wasn’t the weapons themselves that were the problem, it was the states that possessed them’.

Throughout Stuart’s teenage years, and indeed for the rest of his life, he returned to the same question: Spain, Spain, and yet again Spain. As with the rest of the industrial belt of Glasgow, Blantyre was laced with a proud anti-fascist history. The small pit town was home to Thomas Brannan, Thomas Flecks, and William Fox, all three of whom fell on the battlefield in Spain as members of the International Brigades. This local connection to Spain evoked Albert Camus’ famed representation of the ‘Spanish drama’ as a kind of ‘personal tragedy’. Between the age of fifteen and seventeen, Stuart would bear witness to fierce debates outside the local Miners Welfare institute on the ‘politically sore’ topic of war and ‘social revolution’ in 1930s Spain. It was here where he would learn about ‘libertarian Barcelona’, the anarcho-syndicalist CNT, the days of rebellion and street-fighting during the 1937 ‘May Day’ episode, and the brutal military defeat of the Republic in 1939. Yet Stuart would not look back on Spain with a wistful, melancholic gaze. Indeed, he refused to accept it was a lost battle. When he read that two young Spanish anarchists had been executed by the Franco regime for oppositional activities in 1963, he was overwhelmed by the same sense of duty that had impelled anti-fascists to arrive in Spain in 1936.

On Saturday 1 August 1964, Stuart bought a single ticket for the morning boat train from London to Calais and from there headed to Paris: the ‘emigre capital’ of Spain’s Republican and anarchist diaspora. Arriving late in the afternoon at the Rue de Lancry, Stuart met with exiled members of the Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Libertarias (Iberian Federation of the Libertarion Youth). He was to take part in a clandestine mission to Spain organised by the anarchist and CNT-backed ‘Defensa Interior’ committee. Far beyond the more customary exile activity of delivering banned publications, newspapers and leaflets, Stuart was entrusted with transporting two hundred grams of plastique (plastic explosives). If successful, Stuart’s courier mission would have led to the political assassination of General Franco.

‘As things turned out, It was fortunate I planned to be away some time and didn’t buy a return ticket’, Stuart later recalled, as he was consequently apprehended by the Brigada Político-Social on 11 August (BPS, Franco’s political police) and taken into custody. After spending four days beaten and interrogated in the dingy basement cells of Madrid’s police headquarters, Christie was sent to Carabanchel prison where he would stay on remand, while the consejos de guerra (Franco’s special military tribunals’) decided on their verdict. On 5 September, Christie received a note through his cell door stating the details of his sentence: ‘twenty years for military rebellion and terrorism’.

Stuart’s detention reaffirmed his anarchism. In Carabanchel, he found almost instant political fraternity with the hounded, post-civil war generation of anarchists in Spain. But the world of prison challenged his idealism:

‘Before I went to prison my world-view was simple and clear-cut – black and white, a moral battlefield in which everyone was either a goody or a baddy. But the ambiguities in people I came across in prison made me uneasy and I began to question my assumptions about the nature of good and evil. I came to recognise that apparently kind people sometimes had a duplicitous side to them that was amoral, treacherous, self seeking or brutal, while those with a reputation for cruelty sometimes showed themselves capable of great selflessness and generosity of spirit. This didn’t make me cynical, but it did make me less judgemental about my fellow human beings. Also, it was hard to fan the flames of righteous anger in the face of the sheer ordinariness of people’.

The ‘sheer ordinariness of people’ in Franco’s prisons crossed with Stuart’s steadfast rejection of scholarly and popular representations of Iberian anarchism as ‘Manichean’, ‘primitive’, or ‘fanatical’. As Stuart would go on to write, ‘these men and women were not fanatics. They were ordinary rational and dignified people who lived deliberately and passionately, with a vision and a tremendous capacity for self sacrifice; they had been abandoned by the Allies in the “post-fascist” world of the Cold War and deprived of diplomatic or democratic means of resisting Franco’s state terror’.

Stuart returned to England in 1967, following a successful international campaign for his release and some awkward diplomatic pressure. But he never lost sight of those he met in prison. Shortly after his return, he refounded the Anarchist Black Cross (the ABC) with Albert Meltzer. With its initial premises set up in Coptic Street in London, the ABC provided a support network for Franco’s anarchist prisoners while also operating a ‘Spanish Liberation fund’ to subsidise activist groups throughout the country. Its activity was divided into two tasks; first to provide material support, in the form of ‘food parcels and medical supplies’, and latterly to aid the Spanish Resistance movement with ‘everything it needs, including ‘[print] duplicators, typewriters and guns’.

In the years following his release, Stuart would continue to pay heavy penalties for his close affinities with Spanish anarchists. In February 1968, after a series of bombs exploded outside embassies in London, Stuart was raided by the British Special Branch and, thereafter, subject to round-the-clock surveillance outside his London flat. Four years later, Stuart would be indicted on conspiracy charges and was accused of being a member of the so-called ‘Angry Brigade’ (a group responsible for a series of bomb attacks in Britain in the early 1970s) . Along with banks, boutiques, a British army reserve centre, and the 1970 Miss World Contest, the ‘Angry Brigade’ had claimed the machine gunning of the Spanish Embassy and the bombing of a Iberia Airlines office. The reason for Stuart’s arrest in 1972 was because of the string of explosive incidents focused on Spanish targets. From the moment of Stuart’s re-entry into Britain, he was viewed by the Special Branch as the main Anglophone conduit of the Spanish resistance’, and thus guilty by association.

Stuart would be held on remand in Brixton prison, while the trial of the ‘Stoke Newington 8’ evolved into one of the longest criminal trials in English history (lasting from 30 May to 6 December 1972). As Stuart awaited trial, his mind returned to Spain. With the invaluable moral and material support of his wife Brenda, his collaborator Albert Meltzer, and his Black Cross colleague and ex-prisoner Miguel García, Stuart translated into English Antonio Tellez’s ‘Sabaté: Guerrilla urbana en España, 1945-1960’.

After Stuart was acquitted by jury in 1972, he made the decision, following a ‘tip off’ from a special branch officer, to leave London. In 1974, Stuart and Brenda headed to Orkney, where their daughter, Branwen, was born. Here, with the help of Brenda, Meltzer and others, he set up the ‘Cienfuegos’ Publishing House, where he translated and published a number of elusive Spanish texts. Prisoner solidarity work with the Black Cross would also continue. By the mid-1970s, the Anarchist Black Cross had taken on a much broader internationalist remit, aiding political prisoners with parcels, letters and donations not only in Spain, but in France, West Germany, Italy, and Northern Ireland.

Even when the tumult of the 1970s came to a close, Stuart maintained his revolutionary zeal. In 1980, a year after Thatcher’s election, he published a controversial (and still probably illegal) A4 brochure entitled, ‘Towards a Citizens’ Militia: Anarchist Alternatives to NATO and the Warsaw Pact’ (1980). This resulted in an apoplectic response from the national press, who ran with the headlines ‘TERROR BOOKS UPROAR’, ‘SCOTS BOOK OF DO-IT-YOURSELF GUERRILLA WAR’, and ‘ISLAND OF ANARCHY’.

In later life, as well as being an assiduous archivist, writer, and publisher, Stuart became a vital scholarly authority on Spanish anarchism. For professional historians of twentieth century Spain, ‘We, The Anarchists! A Study of the Iberian Anarchist Federation 1927-1937’ (2008), was received as a welcome Anglophone addition on many undergraduate reading lists.

Stuart was not content with writing the political history of the CNT-FAI with a narrowly conceived concept of the ‘political’. His method of writing history was always empirical, but never crudely positivist or detached. This was testament to his open mindedness. He understood that the radical character of Spanish labour movement during the first half of the century was not a result of “ideological brainwashing” or arcane vanguards. Instead, Stuart understood the politics of the CNT-FAI as being rooted in the experience of the Spanish working class.

In 2019, I was contacted by the MayDay rooms regarding a collection of Spanish materials Stuart had recently donated to the archive. I knew I would be familiar with many of the texts in the collection. And sure, I was. But I was taken aback by the number of handwritten inscriptions on his books, messages of deep and profound gratitude, by famed members of the CNT-FAI. I knew the extent to which Spain had left an indelible mark on Stuart; now I was confronted with the mark Stuart had left on the lives of those in Spain.

To the end, Stuart cut through the inertia of our times with a perpetual desire for engagement. Whenever I presented Stuart with finds from the archives, he would inevitably give them life and, in one of his own expressions, provide me with ‘another link in the chain!’. But he always saw his own contribution to History as ‘small’. What I would describe in my work as ‘transnational networks of anarchists’, he would simply call ‘friendships’. He did not consider himself a specimen for study. He lived his politics. He brought people together, many of whom were separated by national and linguistic boundaries. His generosity and loyalty dissolved the remoteness of our encounters. Moreover, despite being half a century older than me, our conversations were rarely unidirectional or top-down. He listened, and if I doubted myself, he built me up, urged me forward.

Above all, Stuart left me with the feeling that even when the odds are stacked against you, you only really need a handful of people to make the impossible happen. Stuart was certainly one of those people.

Jessica Thorne is a PhD student at Royal Holloway, researching transnational anarchist resistance to Franco’s Spain 1950-1975.