The Stuart Christie Memorial Archive was founded in the spring of 2021 and is hosted by the Mayday Rooms. The Archive, brought together by researcher Jess Thorne, preserves Stuart Christie’s private library, personal correspondence, his publishing endeavours, oral testimony, radical ephemera and an extensive online library of anarchist films. In an ongoing process, the archive is being expanded to include a larger collection of oral histories, which will explore the sequence of revolts associated with ‘1968’ and the long winter of reaction that followed in the 1970’s.

Stuart Christie’s life spanned several revolutionary movements, imprisonment and one of the longest criminal trials in English legal history, after which he was acquitted. He died in the summer of 2020, leaving us an impressive political legacy. The archive is a testament to everything Stuart was able to achieve before his untimely death, despite stints in prison and a period of judicious political exile on the rugged archipelago of Orkney. It is altogether a reflection of his political commitment to anarchism, his curiosity and independent-minded determination to challenge old dogmas, all of which often required him to step away from established paths, even within the radical left.

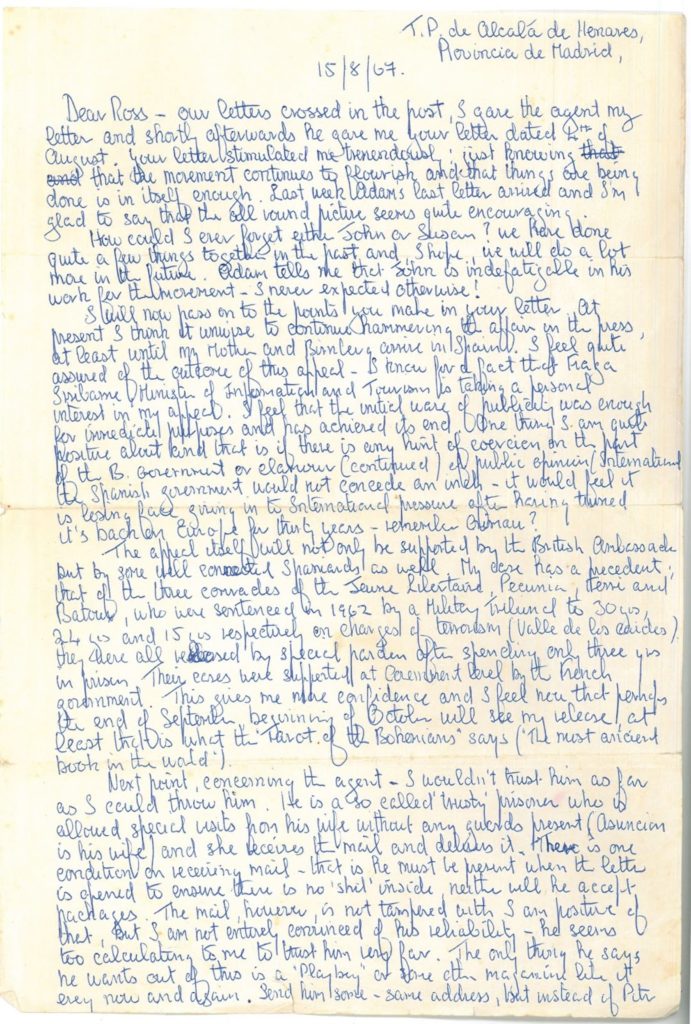

The online archive features ten collections entitled: ‘CND and Committee of 100’, Solidarity: Scotland’, ‘Letters from Spain: The Prison Years’, ‘1968’, ‘Black Flag’, ‘Cienfuegos Press’, ‘Photographs’ and ‘Oral Histories’. These collections include pamphlets, prison correspondence from Francoist Spain, as well as interviews with Stuart’s co-defendants in the ‘Angry Brigade’ trial. Christie had a passion to communicate and share ideas, which is why, when we decided to build an archive in his memory, we embarked on digitalising as much of the physical collection as we could.

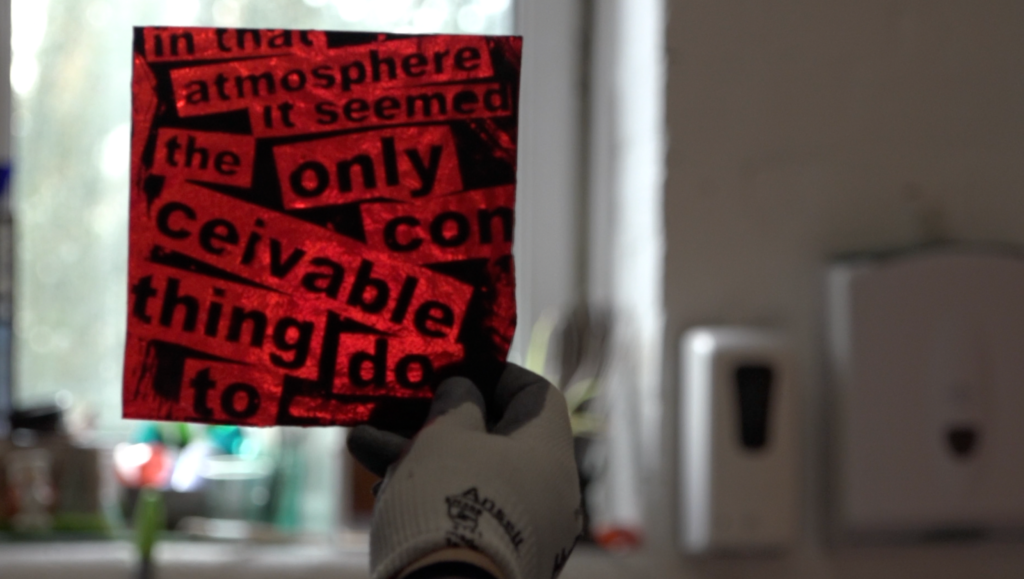

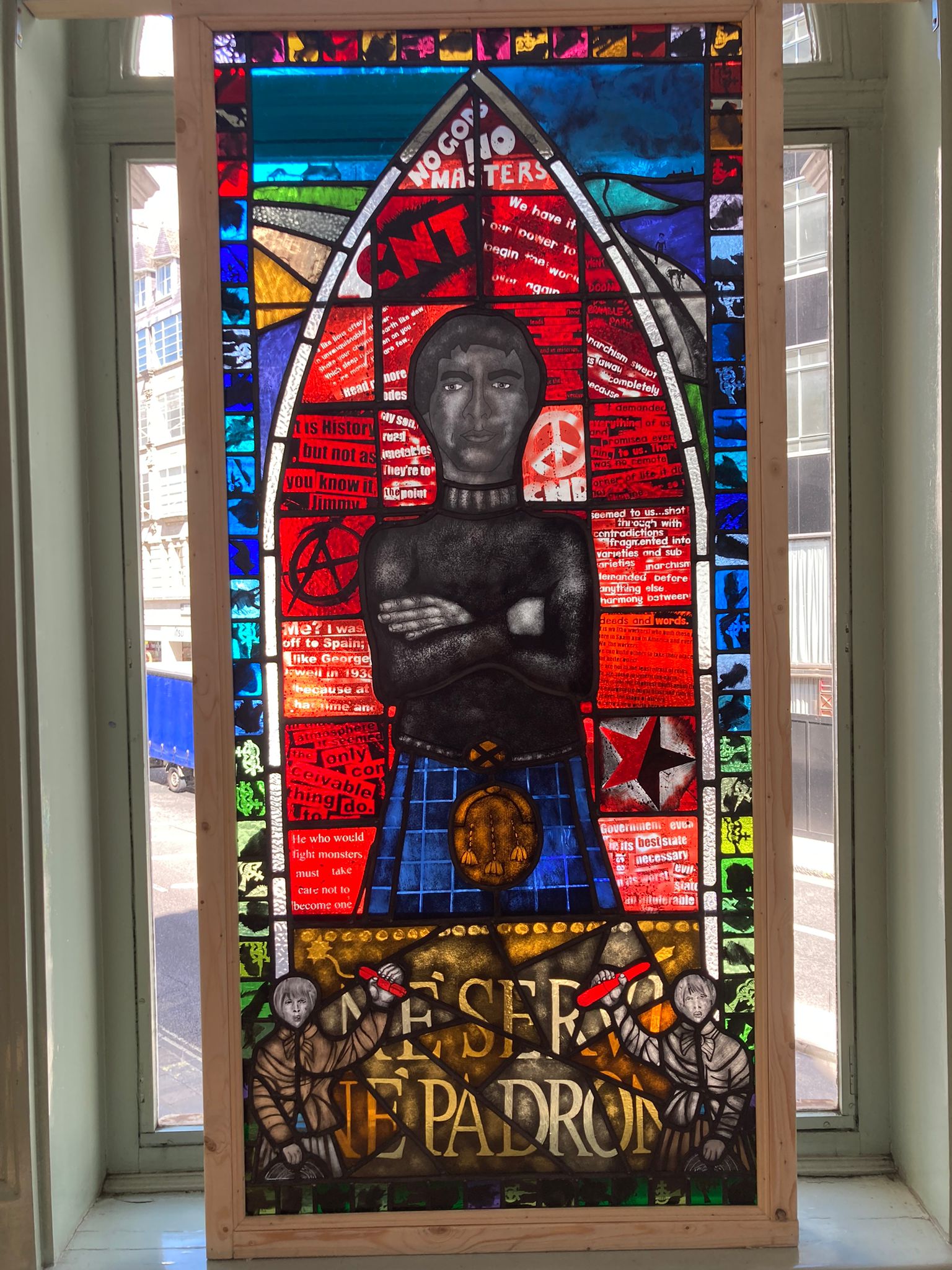

The physical archive and library held in the Mayday Rooms will be accompanied by the installation of a stained-glass window in the reading room, designed by the Glaswegian glassmaker Keira McLean. Stuart would, of course, have been critical of any sort of veneration or saintliness. But hopefully, he would have appreciated the subversive idea of a stained-glass window, that traditional form of religious iconography, being used as a colourful expression of anarchist ideas and anarchist imagery with fragments of anarchist texts and slogans. McLean’s creation is far from earnest canonisation. It’s a playful, tongue-in-cheek tribute to the man whose image is at the centre of the work. It would certainly have amused Stuart, the most prolific of anarchist publishers, to have an image of himself staring out over Fleet Street, directly opposite the old offices of the right-wing Express newspaper group, his nemesis when he returned to Britain from imprisonment in Franco’s Spain. Along with the archive, this homage to Christie not only commemorates Stuart himself but preserves some of the history and rich culture of the broader anarchist movement of the 1960’s and 70’s.

Who was Stuart Christie?

Stuart was born in Glasgow in 1946, in the working-class district of Partick. It was here, at the periphery, where from an early age, Stuart found signs of a different kind of society, one shorn- if not free – of the regulations imposed by state and capitalism. Stuart was a child of Glasgow’s smogged-brown-red tenements and was raised here before the “white heat” of post-war development culminated in mass slum clearances. Scaling the tenement entrances, described locally as ‘caves in the canyons’, Stuart recalled that there was both ‘a happy disregard for anonymity’ and ‘a dynamic community support structure with its own sense of mutual aid’. During his teenage years, Christie moved with his mother to be closer with his Grandparents in Blantyre, a small, isolated pit town, located to the West of Glasgow. Familial ties crossed with class politics in Stuart’s political formation. Along with the influence of his grandmother, the values of whom, Stuart later recalled, ‘married almost exactly with that of libertarian socialism and anarchism’, Blantyre was home in the 1950s to a confident working class. Centred around the NUM and the local Miners Welfare Institute, politics in the local area was synonymous with the Labour Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain. At the age of sixteen, as an apprentice working for a dental laboratory in Glasgow, Stuart had become politically active in the Young Socialists (the youth section of the Labour party). But it wasn’t long before Stuart became disillusioned with the procedural nature of Party life. Once exposed to ‘the machinations and power struggles within the Glasgow Labour Party’, Stuart’s idealistic and reflexive attachment to Party socialism was crushed by its culture of ‘office-grabbing’, ‘local political power plays’ and ‘contending sectarian power agendas’.

The narrowing political horizons of our own time have had the effect of making the post-1945 labour governments in Britain appear Utopian. In many ways, this reflects the impoverished political surroundings of our present. Certainly, economically speaking, the British working class “never had it so good”. Within contemporary memory, it seems that no episode of the country’s modern past deviated as far from its governmental norms as the Labourism of Attlee, Bevan, Benn and Harold Wilson. But it was a bargain reliant on complacency as much as compromise, often forcing emergent shopfloor militancy underground or outside the official unions. Stuart was part of an emerging, predominately young working-class generation which stumbled to the left of this ‘consensus’.

Reflecting the revolutionary ferment of the early 1960s, Stuart’s subsequent turn towards anarchism occurred rapidly. After becoming involved in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, he soon favoured the direct-action approach of the anti-nuclear Committee of 100 over routine marches to Aldermaston led by CND dignitaries. In 1963, he tore up his Labour Party card and joined the Glasgow Federation of Anarchists. A year later, he was making regular trips to London just as efforts were underway nationally to re-found the Anarchist Federation of Britain. It was in Notting Hill Gate, a seedbed of libertarian and bohemian culture – and a focal point for Britain’s emergent neo-Nazi movement– which would lead Stuart towards the site of anarchism’s most durable and most tragic expression: Spain.

After encountering West London’s community of Spanish migrants and exiles, Stuart would become familiar with the revolution of July 1936, the brutal Francoist victory in 1939, and the Allied betrayal post-1945. In the example set by July 1936, Stuart saw an ideal model of workers self-management, which challenged both the moral bankruptcy of social democracy in the West and Soviet Communism in the East. It was this seemingly ‘untarnished’ ideal for which Stuart would cross the Pyrenees in 1964.

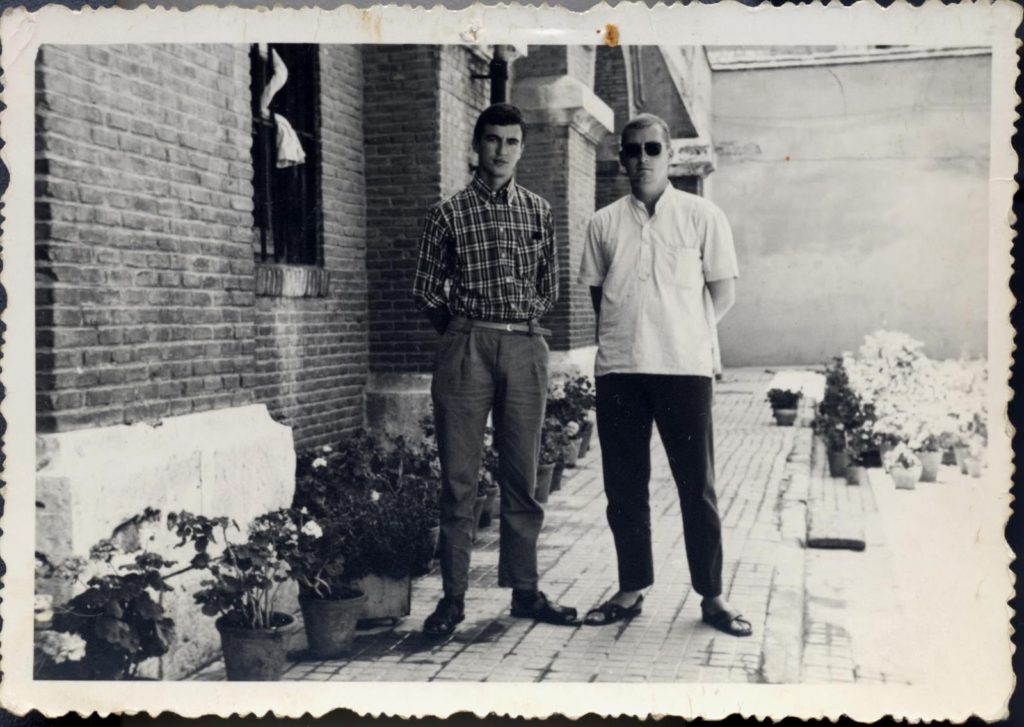

On Saturday 1 August 1964, Stuart bought a single ticket for the morning boat train from London to Calais and from there headed to Paris. Arriving late in the afternoon at the Rue de Lancry, Stuart met with exiled members of the Iberian Federation of the Libertarian Youth. Far beyond the more customary exile activity of delivering banned publications, newspapers and leaflets, Stuart was entrusted with transporting a kilo of plastique (plastic explosives). If successful, Stuart’s courier mission would have led to the political assassination of General Franco.

‘As things turned out, it was fortunate I planned to be away some time and didn’t buy a return ticket’, Stuart later recalled, as he was consequently apprehended by the Brigada Político-Social on 11 August (BPS, Franco’s political police) and taken into custody. On 5 September, Christie received a note through his cell door stating the details of his sentence: ‘twenty years for military rebellion and terrorism’. As the fear of receiving a death sentence by ‘garrote vil’ subsided – the process of slow mechanical strangulation by an iron collar still in use in Spain until 1975 – Stuart resumed political activity in prison.

After Stuart’s early release in 1967, Spain would continue to hang over Stuart – not only as a spectre of revolutionary hope and defeat, nor as the inspiration for Stuart reviving the dormant Anarchist Black Cross, but with his card literally marked by the British Special Branch. Diplomatic files held at Kew concerning Stuart’s imprisonment in Spain show that the British Foreign Office instructed the Special Branch to ‘keep an eye on him…he gives the impression of being an unrepentant anarchist’. In 1972, he faced conspiracy charges in the trial of the ‘Angry Brigade’, a loose urban guerrilla network responsible for a string of bomb attacks against property symbolic of the British establishment. After Stuart was acquitted by jury in 1972, he made the decision, following a ‘tip off’ from a special branch officer, to leave London and head to the rugged archipelago of Orkney. Here he would co-found the anarchist ‘Cienfuegos’ Publishing House with fellow anarchist Albert Meltzer.

Even when the tumult of the 1970s came to a close, Stuart maintained his zeal for provocation. In 1980, a year after Thatcher’s election, he published a controversial (and still probably illegal) A4 brochure entitled, ‘Towards a Citizens’ Militia: Anarchist Alternatives to NATO and the Warsaw Pact’ (1980). This resulted in an apoplectic response from the national press, who ran with the headlines ‘TERROR BOOKS UPROAR’, ‘SCOTS BOOK OF DO-IT-YOURSELF GUERRILLA WAR’, and ‘ISLAND OF ANARCHY’.

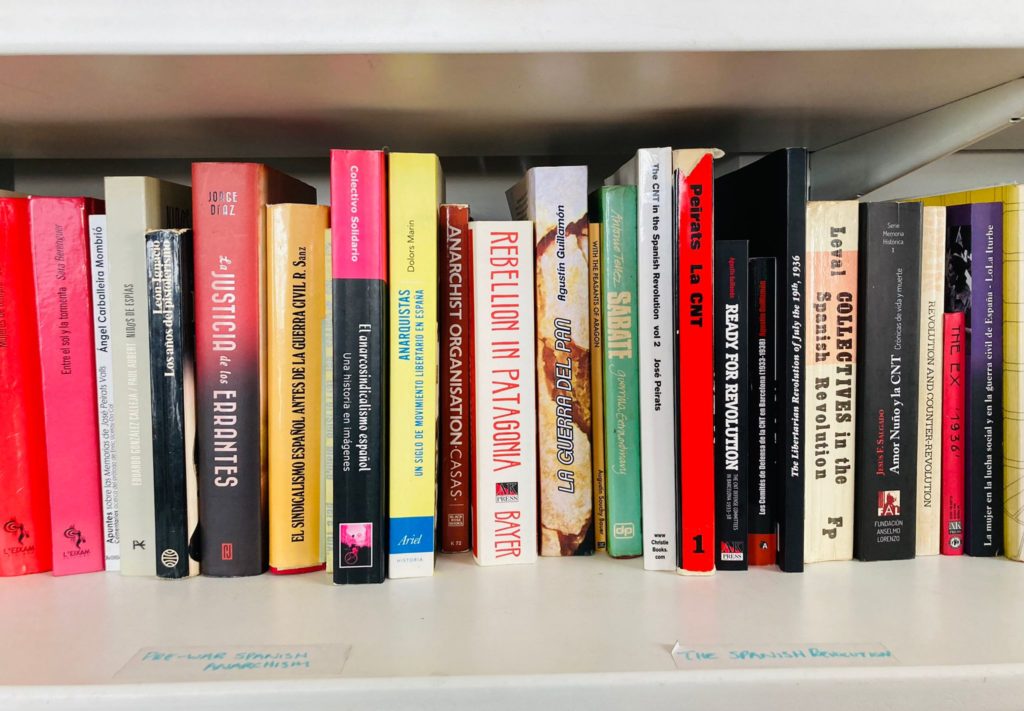

In later life, as well as being an assiduous archivist, writer, and publisher, Stuart became a vital scholarly authority on Spanish anarchism. For professional historians of twentieth century Spain, ‘We, The Anarchists! A Study of the Iberian Anarchist Federation 1927-1937’ (2008), was received as a welcome Anglophone addition on many undergraduate reading lists.

Stuart was not content with writing the political history of the CNT-FAI with a narrowly conceived concept of the ‘political’. His method of writing history was always empirical, but never crudely positivist or detached. This was testament to his open mindedness. He understood that the radical character of Spanish labour movement during the first half of the century was not a result of “ideological brainwashing” or arcane vanguards. Instead, Stuart understood the politics of the CNT-FAI as being rooted in the experience of the Spanish working class.In ‘The Wretched of the Earth’, the psychiatrist and political philosopher Frantz Fanon remarked that ‘the presence of an obstacle accentuates the tendency towards motion’. Stuart’s life was one that insisted on motion. Against the dark fantasies of Cold War McCarthyism and the very real threat of nuclear fallout, Stuart insisted on the possibility of realising anarchism’s dream. As the final words of ‘Floodgates of Anarchy’ (1970) read: ‘Backward, indeed, to the free city, with its guilds of craftsmen and groups of scholars, its folk-meeting and loose federal association. But forward to the use of technology in its proper place, at the service of man… Backward to the workers’ councils of the Russian and German revolutions; the free communes of Spain, Ukraine, Mexico; the occupation of the places of work in France and Italy…Forward to the Utopia of William Morris, now well within the reach of man’.

Links and Resources

Other Archival Material:

Stuart Christie Film Collection @ Kollectiva

Archived version of Christie Books website

Kate Sharpley Library

Writings about Stuart:

Red Years, Black Years By Jessica Thorne

Obituaries:

Duncan Campbell in The Guardian (17/08/2020)

Stuart Christie, 10 July 1946-15 August 2020, By John Barker

Death of a Mentor by Jessica Thorne