In 1974 Lucas Aerospace announced restructuring and cuts to jobs. Around half of the company’s output supplied military contracts based on state funding. In response to the cuts and the offshoring of jobs, the workers responded to this by organising themselves into a Combine. The Combine spent two years developing a proletarian corporate plan in which plants used to make weapons could be recommissioned to produce socially useful goods. Plans for socially useful items were drawn up by the workers, and included cutting edge green technologies such as wind turbines and hybrid power packs. Ultimately, though, the Labour government and the unions were unable to put enough pressure on the company management, and despite the depth of the plans created by the workers they were never implemented. Eventually many workers from the Combine were able to set up the Centre for Alternative Industrial Technologies. The Lucas Plan Archives contains letters and minutes, exhibitions and newsletters, newspaper cuttings and campaign materials, as well as materials produced towards the corporate plan.

Our collection can be found here

More details about the Lucas Plan can be found here:

https://lucasplan.org.uk/story-of-the-lucas-plan/

Combine News

Lucas Aerospace Combine Shop Stewards Committee

(March 1975)

The first of this month’s archival scans: a copy of the Combine News, produced by workers at Lucas Aerospace. While facing cuts after the oil crisis, they started to organise to shift production from military contracts to socially useful goods.

After the economic crisis of the early 1970s many workers saw their jobs threatened. At the time approximately half of Lucas Aerospace’s production was for defence contracts for the British Military. Amid the economic turmoil the company planned to lay off staff in order to stay afloat, so workers across the various plants came together to create the Lucas Aerospace Combine Shop Stewards Committee. The Combine acted as an agitational front within the various plants that Lucas owned, sporadically producing its own newspaper, helping workers to informed about the struggle to oppose redundancy and increase wages at the company

The front page of this early copy of the newspaper shows a concern over wages for engineers working in the plants. It also includes a report of a 13-week strike that had taken place at the Burnley plant, and increasing concerns about pensions. But there are hints of the larger historical role that the Combine would play. Included is a photograph of a meeting that took place between Tony Benn, who was Secretary of State for Industry in the newly formed Wilson government and members of the combine. Benn pushed for nationalisation of failing industries, and the Combine met with him to see if he could help save their threatened jobs.

Benn is said to have told the members of the Combine that many workers from many industries were asking the same of him at the time, and that he needed their help to find a way to save their jobs. Below the photo of Benn is a brief mention of how nationalisation could take place through the diversification of the sorts of work undertaken at the Lucas plants, and the possibility of “socially useful production”. This idea would develop, over the course of the next year, into The Lucas Plan – a worker-led corporate plan, under which Lucas would shift away from military engineering, and towards engineering for social needs, including medical supplies, new public transport infrastructure, and heating systems for housing estates.

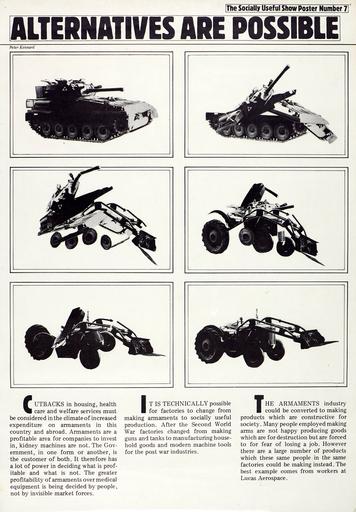

Alternatives Are Possible

The Socially Useful Show Poster Number 7

As fashion houses rush to produce PPE and F1 teams make ventilators, today we look back at how workers at Lucas Aerospace thought about converting military production to make kidney machines in the 1970s

The workers at Lucas decided that the best way that they could save their jobs was to think about how their skills and the machines at the factories could be used to fulfill real social needs, as military contracts declined. They began by writing to professors and product designers but got little response. So they decided that they would do it themselves. The Combine solicited designs for new products from engineers across the company. The result amazed them, as over 150 designs poured in. They included everything from new vehicles to medical devices. As the poster explains, there was a precedent for this type of diversification in production: “It is technically possible for factories to change from making armaments to socially useful production. After the Second World War factories changes from making guns and tanks to manufacturing household good and modern machine tools for the post war industries.”

But there was more to the politics of this than just protecting jobs. Everyone in the company understood that the arms race of the previous decade meant on the one hand the mutually assured destruction if the cold war ever moved beyond a skirmish, and on the other hand the perpetuated the violent and hegemonic dominance of those countries that were richest. The attempts to shift production at Lucas brought workers there into conversation with international movements for peace and anti-militarism. Meanwhile, the economic crisis had exposed the perverse fact that it had become profitable to make killing machines but that there would never be such profit in creating machines to keep people alive.

Regardless of profitability, the workers understood that the matter was in fact a question of government priorities: “The Government, in one form or another, is the customer of both. It therefore has a lot of power in deciding what is profitable and what is not. The greater profitability of armaments over medical equipment is being decided by people, not by invisible market forces” This sentiment rings all too true today, as after a decade of austerity in which murderous politicians claimed that “there is no alternative” as they exculpated themselves. Today companies are frantically trying to convert production: high end fashion labels attempt to make personal protective equipment for the NHS, while Formula 1 teams are trying to produce ventilators. Although the Lucas Plan would ultimately fail, one of the few products that eventually went into production at the aerospace plants was kidney machines.

This poster is drawn from a set called ‘The Socially Useful Show’, which was created as an exhibition to teach others about what the workers had planned at Lucas. The posters were designed by a number of radical political artists: this one includes photomontages by Peter Kennard. Kennard’s work draws on the tradition of radical photomontage, which started in the 1920s with the likes of John Heartfield and Sacha Stone. He has long been associated with creating art for anti-militarist causes, and during the 1970s and 1980s worked closely with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Here his images reinterpret the image from the Book of Isaiah of “beating swords into ploughshares” for the machine age, as a tank is transforms into a tractor.

Kennard would continue to create work about arms conversion, using the designs from the Lucas Combine’s alternative plan. These were published in the book About Turn: The Alternative Use of Defence Works in 1986.

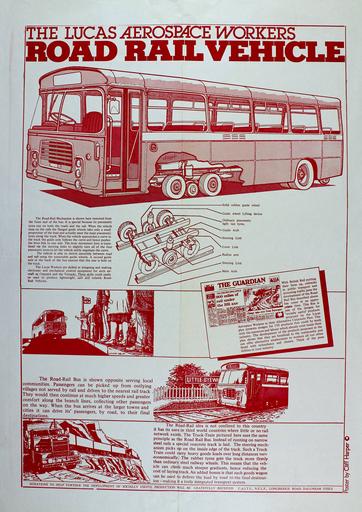

The Lucas Aerospace Workers Road Rail Vehicle

(1980)

THE ANSWER IS THE RAIL BUS!

This scan looks at the hybrid road-rail vehicle designed by workers at Lucas. It shows how in opposing the motive of profit, worker-led planning could help to design green infrastructure we all need.

The workers at Lucas Aerospace became aware that allowing the free market to determine production led to short term thinking, and the undermining of infrastructure that could improve everyone’s lives. Among the designs that were part of the Lucas Plan were new green technologies such as wind turbine and hybrid fuel cells for cars. The workers also took a global view of technological need, developing systems that could be used flexibly in poorer countries, such as a universal pump.

But perhaps one of the more unusual technologies they designed with both green tech and global need in mind was a hybrid road-rail vehicle. The idea was that this railbus could travel around on roads, picking people up near their homes, make a long journey by rail, and then again travel on roads to drop people off at their destinations. As this poster shows, the idea was aimed at “countries where little or no rail network exists.”

But to an extent this meant Britain as well. By the 1970s the British railway system had been devastated by a series of reports and policies instituted while Richard Beeching was the chairman of British Rail, during the early- to mid-1960s. The “Beeching axe” meant that 6000 miles of British railway lines were put out of use over the course of a decade. Stations and railway lines that served rural communities were cut off. And these brutal decisions made simply because these lines not economical. This situation left many people who lived in rural locations cut off, and there were continuing cuts into the 1970s, leaving further communities isolated. It is strange to think today how clear it was 50 years ago that the introduction of economism into public services so obviously undermined the provision of transport needs, not least when neoliberalism has since then has proclaimed that profitability is a gold standard in the provision of public services and the design of infrastructure.

By 1978 members of the Lucas Combine had established the Centre for Alternative Industrial and Technological Systems (CAITS) at North London Polytechnic. They had decided that what they had learnt about worker-led planning and design should be taught to others in the trade union movement. While at CAITS they even made a prototype of the hybrid road-rail vehicle, which travelled around the country promoting the Lucas Plan.

Although the Lucas Workers’ hybrid road-rail vehicle never went into production, it wasn’t so far away from what would happen. By the early 1980s British Rail had commissioned 40 “Railbus” vehicles. These cheap rolling stock, commonly called “pacers”, were based on the design of a bus, with a set of wheels on each corner, and were an attempt to put routes that had little traffic back to use. An advert placed by British Rail in The Times in 1982 proudly proclaims, “The Answer is the Railbus.” The Pacers continued to be part of the British Rail rolling stock, finally being decommissioned only in the last two years.

This poster was designed by the anarchist illustrator Cliff Harper, who created a number of posters for ex-Lucas workers who were working at the Centre for Alternative Industrial and Technological Systems.

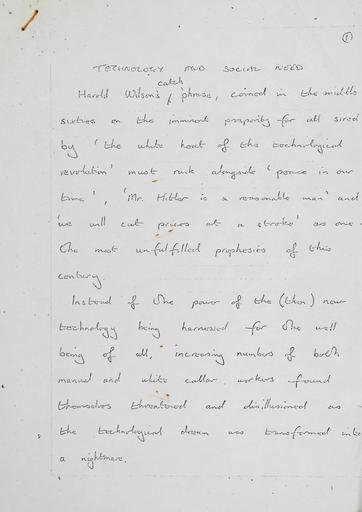

Technology and Social Need :A Manuscript by Phil Asquith

This is a manuscript of an essay on Technology and Social Need written by one of the engineers working at Lucas Aerospace. It is an excoriating critique of the promises of technological progress and their mirror image in the reformism of the trade union movement.

“Today, on the one hand we have a level of technology which produced Concorde yet people are allowed to die of hypothermia for want of cheap urban heating systems or of renal failure for want of a kidney haemodialysis machine, when there are thousands of scientists and engineers being allowed to rot in the dole queue.”

Bourgeois society has always demanded that theory arrive from academicians sequestered away in libraries and ivory towers. The closest these people come to production is as overseers, or perhaps as putative designers and architects of the labour process. But an element of the idea that theory is, in itself, bourgeois has been an effort to silence the sorts of the thinking that happens on the factory floor.

This essay, written by one of the engineers working at Lucas Aerospace, shows what was being silenced. It is an excoriating critique of the doctrine of economic progress, taking aim at the nonsense proposal by Harold Wilson that “the white heat of the technological revolution” would bring about imminent prosperity for all. Instead, it sees clearly, the intensification of industry as leading to the intensification of labour on the one hand, and the junking of workers into dole queues on the other. Asquith, who wrote this essay, also recognises that there is a correlate within the labour movement to the myth of technological progress.

For as much as technology seemed to promise progress, the trade unions took a reformist line in protecting jobs without ever questioning what those jobs are for: “when defence cuts have been made, union leaders have inevitably argued for the retention of the particular project to protect their members’ jobs. Thus our members have always been presented with the false choice between military production or the dole.” Against this false opposition, the essay offers an exposition of The Lucas Plan, which entailed not just the production of socially useful products, but more profoundly, “contains proposals for the fundamental changes in methods of working. Not merely to obtain “better butter from contorted cows” as with the philosophy of job enrichment schemes, but to release this country’s greatest asset, the skill, ingenuity and creativity of its workforce by breaking down the hierarchical divisions between job functions and by allowing people to work in humane conditions at a civilised tempo.”

Although just a draft, this manuscript shows the shape and the fire of a practical-critical response to the crisis of the 1970s. Many of its arguments are as pertinent today as when they were originally made. But even more, today, theory has returned to the universities, where it continues to rot. Perhaps we should find thinking once again on the shop floor or in the dole queue!

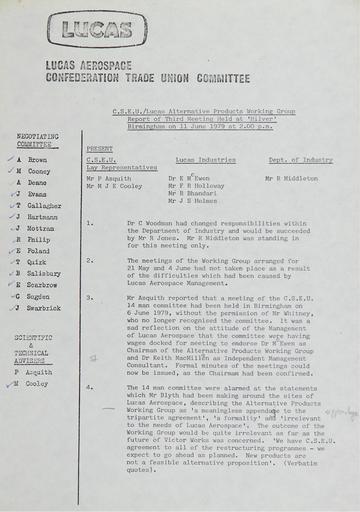

C.S.E.U/Lucas Alternative Products Working Group,

Report of the Third Meeting Held at ‘Hilver’, Birmingham

11 June 1979 at 2.00pm

In the last of our series of archive logs about The Lucas Plan, today we look at their work at the moment of defeat, as they were sold out by the Labour Party and their Trade Union, as Management refused to introduce their products designed for a greener future.

Defeat alters the tense of history. The failure of a project conjures into the world new spectres of that which could have been but which did not come to pass. These spectres do not just form of counterfactual present, they are not some shimmering counter-future hidden behind the future we were instead forced to live out. Instead, defeats send shards of the past – of what could have been – into the present of our lives, to be taken up as unsuspecting weapons in history. To discover them as weapons means to umderstand the nature of the defeat; to reanimate ghoulish enemies only to this time to dispatch with them more sharply, in order to alleviate the long catastrophes through which they have forced us to live and to die.

The defeat of The Lucas Plan involved many such ghouls. And as a defeat it wasn’t alone: 1979 is a knot in the past, in which so many defeats are gathered; the unions crushed, the left and the women’s liberation movement fragmented, Thatcher ascendent, the collapse of industry guaranteed. This final document in our archive log are minutes to a meeting that took place among members of the Lucas Combine in 1979, just as it was becoming clear that their struggle was lost. Late in the previous year, during the Winter of Discontent, negotiations between the trade union – the CSEU – and management at Lucas had started to break down. During the CSEU conference it was agreed that a “14 man committee” would represent the workforce at Lucas. As can be seen in the minutes of this meeting, by the middle of the following year the management of Lucas were refusing to recognise this committee.

But management were not the only villains of the piece: the CSEU were working behind the backs of the workers to make separate agreements with management. Management said of one factory, “We have CSEU agreement to all of the restructuring programmes – we expect to go ahead as planned. New Products are not a feasible alternative production.” while dismissing the Alternative Products Working Group as “a meaningless appenage to the tripartite agreement”. “a formality” and “irrelevant to the needs of Lucas Aerospace. Nor were the Labour Party to help. The meetings between Lucas Workers and Gerald Kaufman, who was on the right of the party, came to little fruition.

Despite the fact that from this point onwards Lucas Management would refuse any further attempts of the workers to realise their corporate plan to create alternative products, the workers continued to develop them. The minutes here include discussions of hybrid power packs for cars, control systems, heat pumps, magnetic break retarders, industrial gas turbines, and even hydrogen fuel cells and robotic devices. Many of these commodities would go into production by other companies. Many of the workers who were part of the Alternative Products Working Group went on to work for the Centre for Alternative Industrial and Technological Systems at North London Polytechnic. But these are not conclusions: they are moments in a history that remains a site of contestation – they are pieces of the past that we must take up as weapons in struggle, that shifts back and forth between what could have been and was not, and what ultimately came to pass: and running through that history are transformations of need and technology, and the promise that in the fight these may be reconciled.