Archive log takes us back to the world of the radical underground of the early 1970s.

Muther Grumble was a radical paper produced in Durham for two years in the early ‘70s. Containing everything from the intrigues of local politics, despair over growing technocracy and unemployment, and a history of fairies and giants in the North East!

Our collection can be found here

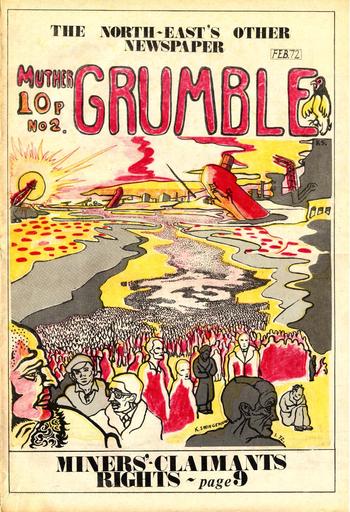

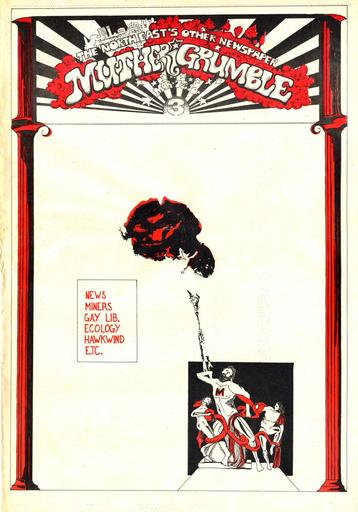

Muther Grumble, Issue 1

December 1971

Details and pdf here

It has become too easy to imagine the counterculture as a puff of smoke on the horizon of history. Some nebulous network of hippies appears for a brief instant only to quickly dissipate, ineffectively, into catastrophes of historical inevitability. Every attempt to grasp the moment seems to fail, or at best to fall into a peculiar Romanticism, like an overexposed photograph that claims to have captured an image of something precisely at the moment of its disappearance. Muther Grumble, a newspaper that was produced between 1971 and 1973, is both an archetype of this momentary swelling of the Underground, and at the same time gives the lie to any attempt to split its history from wider social motions.

The words in this issue are barbed in ways that remain familiar: the formalism of Leninists is picked apart. So too are the proclamations of social democratic trade unionists in a time of rising unemployment: the TUC’s “Right to Work” slogans and placards emblazoned with ineptitudes like “Happiness is Job-Shaped”. Hippies too are pillaried: the “freer consciousness” of the perpetual dope smoker is grilled by a Marxian argument for a revolution in praxis and not just in the mind. At the end of the issue a meditating hippy is caricatured amid the genocide in Bangladesh (profits from the sale of the newspaper – if there were any – were sent to refugees from the Bangladeshi war of independence.

The contents of the paper too are unusual: they include brief theoretical essays that tend sometimes towards prose experiments, to investigative reports of political intrigue in the local Durham Labour party, to a critique of the latest John Lennon album by someone who knew him personally, and a political call to the left on how to respond to the Troubles in Ireland. The irreverance of the moment is given shape by a description of “Operation Rupert”: a call for the underground to disrupt the massive Christian ‘Festival of Light’ in London, which turns out disorganised and hilarious. Cliff Richard gets eggs chucked at him. The Gay Liberation Front tussle with cops: “Meanwhile a fuzz was having the pleasure of being kicked in the nuts by an irate nun in drag. Big boots and hairy legs under her habit. Too few freaks turned out to make an arrest impossible, meanwhile the underground are happy with the myth that was Operation Rupert.” More importantly though, much the writing begins a critique of the new technocracy, linking together the shifts in production at that moment to rising unemployment. Some of the reflexes of this critique are recognisable: a regression into local myth, in which the giants and fairies of County Durham have their stories unearthed; a heady psychedelic existentialism; a wicked situationist verve.

But at the same time there is an attempt to reach out – to break down the divides between freaks and straights: community organising and local papers full of people’s everyday lives. A promise of help with benefits claims, struggles with landlords. Even the possibility of people dropping by the newspaper office if they need advice, for everything including questions on contraception, unwanted pregnancies, drug difficulties (busts, bad trips, hang-ups and addictions) and racial discrimination.

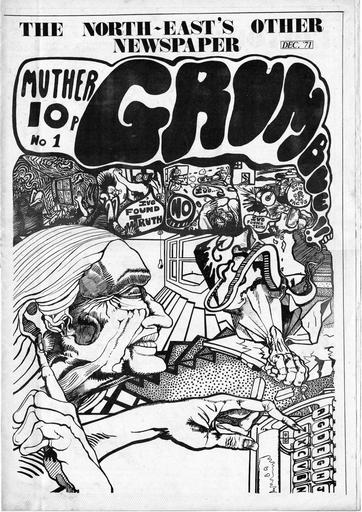

Muther Grumble, Issue 10

February 1973

“CRIME”

Details and pdf here

Muther Grumble’s issue on Crime from February 1973. Read the exposés of new forms of violence used by the state to undermine the underground, benefits claimants, striking miners. Here is the story of political policing in Britain, and how a criminally corrupt establishment tried to crush a movement.

“Perhaps we should get more angry.” This sentence must have been written with a wry smile with its nod to the Angry Brigade, in the wake of their long trial. By the beginning of 1973 all of those elements that had coalesced in Muther Grumble – hippies, striking miners, Marxist elements from the student movement, benefits claimants – were under sustained attack. The state was increasingly finding ways to criminalise the underground:

“A look at some recent events and a general pattern begins to emerge that indicates that pressure from the establishment is increasing far more than the pressure on it. For instance when a person or group of people is seen by the authorities to be a threat to their stability, it is becoming increasingly common for prosecutions to be brought for conspiracy, incitement or something equally non-specific. In fact there are a whole group of laws and acts, some new some archaic, which the authorities can use to suppress those they see as a threat. In other words, if they want to get you they don’t need to wait till you commit a ‘crime’. These are the laws relating to Official Secrets, Conspiracy, Incitement, Drugs, Censorship, Obscene Publications, Court Injunctions, and Special Powers, Housing Finance, and Industrial Relations Acts. Nearly all prosecutions under these laws could be described as political.”

But this violence not just a matter of finding the right charge to condemn the lives of the underground; it was part of a process in which the state at every level bolstered informal legal violence against those who wanted to change the world. By the end of the student movement the Special Demonstration Squad had been established. In the early 1970s political trials were brought against several underground newspapers (most notoriously the Oz trial), while Robert Carr’s Industrial Relations Act had put an end to wildcat strikes. Meanwhile, the colonial policing of Ireland was closer to home than ever. At the same time, individuals were subject to increasingly draconian sentences for possession of marijuana. One article in this issue details such a bust in which David and Sally were given 36 and 21 month sentences for possession of weed and acid, after the Drug Squad and Special Branch smashed down their front door and beat up Dave.

But their story is less than usual: most often this extra-legal violence was less about securing a conviction than justifying police violence, holding people on remand, The Crime issue of Muther Grumble testifies to how well understood it was by all those in different movements – from students, to miners, to drugged up dropouts – understood this new organisation of state violence. For them, the Angry Brigade trial became an avatar: a show of strength by the state, in running through a political stitch up. But for those who had been convicted, the paper describes the establishment of a new Prisoner solidarity and reform group, PROP.

So this issue – having understood the accusation of criminality to be entirely political – engages in an attempt at recrimination. Under the titles, “PORN”, “MURDER”, “ROBBERY”, “RAPE” the crimes of the establishment are exposed one by one. There is also plenty of investigative work on the Poulson scandal, which had originally been a scoop for Muther Grumble (and ultimately led to the toppling of a minister), alongside further articles on corruption among local officials. If calling something a crime had become a political accusation, here is the backlash from below!

Alongside this are the usuals from Muther Grumble: News about music (David Bowie and Rock ’n’ Roll revival), a lovely miners song from the 1880s about an overproductive but stupid who dies eating a greasy dishcloth, a semi-situationist reflection on Christmas, and listings of events all over the North East.

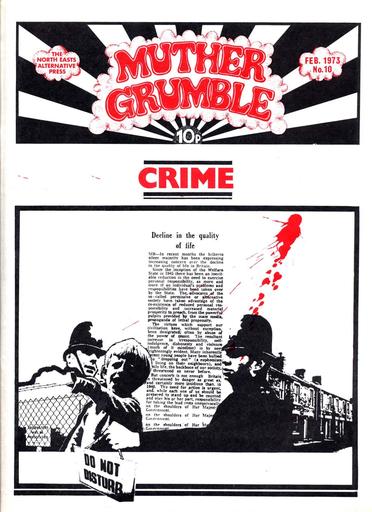

Muther Grumble

Issue 3

February- March 1972

Details and pdf here

Issue 3 of Muther Grumble, an underground newspaper from the North East in the middle of the 1972 miner’s strike!

he sculpture of Laocoön and his sons remains remarkable. The ancient work of art, excavated in Rome at the turn of the 16th century, formed the beginning of the Vatican’s art collection. Since then the figure, depicting the agony of Laocoön as his sons are coiled by serpents sent by the gods, has had a propitious history. The statue became the object of the great debates in aesthetics during the 18th century: Winckelman posed the question of how such a depiction of suffering could be considered beautiful; Lessing would polemicise against him, discovering the sculpture as the site of convergence – and disarticulation – between the temporal arts (poetry and music) and the spacial arts (painting.)

But the sculpture had a second history on paper. Those who could not make a pilgrimage to the Vatican would, by the 17th century see it in etchings. The image wrapped around the world on the basis of the technologies of printing that were founded in those same years that the marble was excavated. But the height of this history came with William Blake, whose engraving of the Laocoön group from the mid-1820s is one of his most extreme and extraordinary works. There Laocoön is reinterpreted as Jehovah, and his two sons as Adam and Satan. Around the figures are inscribed verses and slogans in English, Hebrew, Latin and Greek. “The Eternal Body of Man is the Imagination, that is God Himself,” “Where any view of Money exists Art cannot be carried on, but War only”, and “Christianity is Art & not Money. Money is its Curse.” Blake’s prosecution of the classicism of catholicism, drenched in the money of art and the artifice of money, against a more simple, natural-supernatural art and Christianity, proposes the solution of the rest of his oeuvre: a new Christian demonology of local gods, founded in the commons, befallen by the monstrous greed of Capital. And befallen is how he would depict Laocoön, not tense in agony, but infinitely sad.

How strange it is to add to this history of agony in print with the cover of an underground newspaper from Durham in early 1972. Here the figures appear cartoon-like. The tension of the contrapposto reduced to a stoner’s dance; the figures camp and balletic with red snakes slinked around their backs. Out of Laocoön’s arm an artillery turret shoots into the sky. Above them an ominous black and red cloud hovers. Pinned to the nowhere of a background a sign reads:

NEWS

MINERS

GAY LIB.

ECOLOGY

HAWKWIND

ETC.

The image is framed by stage curtains – a nod to the psychedelia of the “Magic Theatre” issue of Oz Magazine, which had appeared three years earlier.

So what are we to make of this image and its grand intellectual history, appearing again here and now? Certainly the image would not be recognised by most of Muther Grumble’s readers: and this issue in particular indicates something of a divide: on one side the are the the effete university intellectuallism recast in the argot of freakery; on the other the industrial strikes and the powercuts. While it is not the case that the students are intellectuals and the miners are not, it does hold true that the students were rather more interested in what was happening in the struggles in the pits than the miners were in the drug-addled intrigues of Durham JCR. Agitationally there is a ferocious ultraleft sensibility: “the victory is the miner’s – not the N.U.M.’s, and especially not the T.U.C.’s.” Elsewhere the great traditions of the working class are called up from sung but unspoken history, as 19th century miners songs are catalogued and reproduced; the strikes of the 1970s are given voice in the dialect and movement of a new 19th century proletariat. But now they are surrounded by different cultural phenomena: a small report on the Sunderland School’s Action Union – a veritable failure as only 10 people are interested in joining; and the newly formed Gay Liberation Front against the homophobic violence of the law. For those of us with an passion for archiving political ephemera, it is even reported in the paper (with no explanation) that the Texas Memorial Museum has started a collection of political bumper stickers. And then there are practical questions: a page dedicated on how to respond to being arrested.

But what of Laocoön? Perhaps Blake, with his straight-talking slogans didn’t quite say what he meant. Where he dismisses all art where there is a view of money, is the question not truly one of quite the opposite: of art in the situation of poverty? Perhaps money and poverty are one and the same: the scandal of art dripping in money is thrown into relief only by those who have none. The great machine is only known as evil by the broken bodies it churns out. A tiny report mentions how “the miners union has never seriously campaigned for higher pensions for its members, as not many live past retirement age.” But in the bourgeois world knowing this evil has always been given an aesthetic twist. Isn’t Winckelman’s question, of how such agony can be beautiful, not the very central question of all bourgeois “appreciation”? Is all bourgeois art not just such a theodicy for the eyes? It is not the agony of a man brought low by gods, but the agony of production in which the beautiful semblance covers over the hidden violence of human destruction. Such a thought brings to mind the other great interpretation of Greek sculpture from the 1970s: Peter Weiss’ interpretation of the Pergamon Alter in the Aesthetics of Resistance, where the tort bodies of gods and titans are fashioned after the bodies of workers hewing the very stone from which the alter would be built. But here, as Laocoön and his sons are redrawn, there is finally repose. It is a different opposite to hard work of hewing coal from a pit: it is the strike, the stoner’s dance of unemployment, increasingly common, in those early months of 1972.