In 1974 Lucas Aerospace announced restructuring and cuts to jobs. Around half of the company’s output supplied military contracts based on state funding. In response to the cuts and the offshoring of jobs, the workers responded to this by organising themselves into a Combine. The Combine spent two years developing a proletarian corporate plan in which plants used to make weapons could be recommissioned to produce socially useful goods. Plans for socially useful items were drawn up by the workers, and included cutting edge green technologies such as wind turbines and hybrid power packs. Ultimately, though, the Labour government and the unions were unable to put enough pressure on the company management, and despite the depth of the plans created by the workers they were never implemented. Eventually many workers from the Combine were able to set up the Centre for Alternative Industrial Technologies. The Lucas Plan Archives contains letters and minutes, exhibitions and newsletters, newspaper cuttings and campaign materials, as well as materials produced towards the corporate plan.

Lucas Plan

THE LUCAS PLAN STORY

In 1976 the Lucas Aerospace Combine Shop Stewards Committee produced an Alternative Corporate Plan for Lucas Aerospace that advocated the production of social useful products. This was in response to management announcing the need to cut jobs. The Combine was a representative body of staff and manual worker unions on all the fifteen sites throughout the U.K. It had been established by the shop stewards to enable the workforce to have a coherent and unified voice when responding to managements corporate view on wages, pensions, manning levels and other such issues. The shop stewards had realised though experience how management had used divide and rule tactics when negotiating on an individual site and craft union basis.

Following a period of expansion, in 1974 Lucas Aerospace along with other aerospace companies announced the need to restructure the company as a consequence of ‘increased international competition and technological change brought about by the need to introduce new technology’. Around half of Lucas Aerospace output supplied military contracts. Since this depended upon public funding, as did many of the civilian contracts, the Combine argued that state support would be better put to developing products that society needed, rather than the state supporting workers through paying redundancy money when they were put out of work.

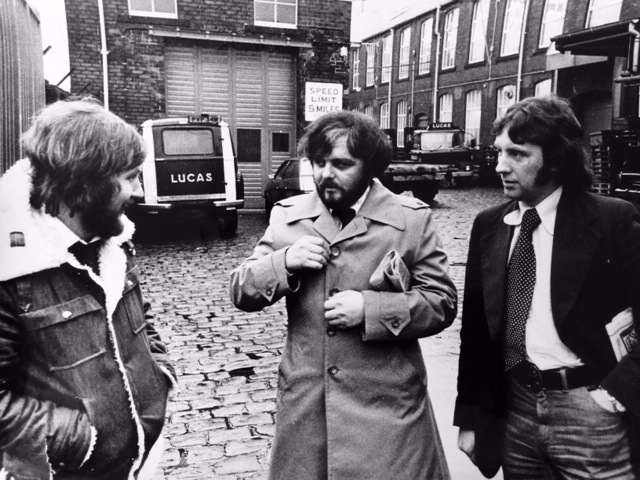

The idea of the Combine’s Alternative Corporate Plan came about as a result of a meeting held with Tony Benn at the Dept. of Industry in November 1974. Thirty-four Combine delegates met with Benn in an attempt to persuade him to include Lucas Aerospace in the nationalisation of the aerospace industry. Benn indicated he did not have the power to include Lucas Aerospace in the nationalisation proposals; however he suggested that the Combine should draw up an alternative corporate strategy for the company. This suggestion started a process which resulted in the Combine drawing up the Corporate Plan.

Initially the Combine approached outside organisations for suggested products. After receiving only three replies from 180 outside bodies, the Combine circulated questionnaires to the workforce requesting product suggestions which answered a social need and could be produced using the workforces existing skills and plant technology. Emphasis was also to be put on the way the products were to be made, making sure that workers were not to be deskilled in the process of producing them.

150 product ideas were put forward by the workforce. From them, products were selected to fall into six categories: medical equipment, transport vehicles, improved braking systems, energy conservation, oceanics, and telechiric machines. Specific proposals included, in the medical sector, an expansion of 40% in the production of kidney dialysis machines, which at that time were being manufactured on one of the L.A. sites. The Combine ‘regarded it was scandalous that people could be dying for the want of a kidney machine when those who could be producing them are facing the prospect of redundancy’. In the energy sector, proposals included the development of heat pumps, solar cell technology, wind turbines and fuel cell technology. In transport, a new hybrid power pack for motor vehicles and road-rail vehicles. Later, the Combine produced a road-rail bus, which toured the country.

The proposals were rejected out of hand by L.A. management, indicating they would not diversify from aerospace work, even though they had clearly indicated that aerospace work was in decline, and the existence of marginal industrial and medical equipment already being carried out on some of the sites, which could have been built upon.

The Combine’s Alternative Corporate Plan received worldwide support from a multitude of organisations including those who would not normally support trade union activity. Combine shop stewards attended numerous meetings in the U.K. and visits abroad to Sweden, Germany, Australia and USA. In 1981, Mike Cooley, a member of the Combine, received the Right Livelihood award, the money from which he donated to the Combine. In addition, the Combine was successful in attracting funding from charitable bodies, which enabled us to set up the Centre for Alternative Industrial Systems (CAITS) at North East London Polytechnic and the Unit for the Development of Alternative Products (UDAP) at Coventry Polytechnic.

While individual Trade Unions and the Labour Government supported the Combine’s Plan in principle, there was neither the structures in place, nor the political will, to put pressure on Lucas Aerospace management to negotiate with the Combine to implement the Plan. An opportunity was lost to make a company receiving public money accountable to the community in which it served.

Forty years on, the products put forward by the Combine in their worker’s plan are now mainstream. Two examples (there are numerous others) of this are the production of hybrid power packs by most vehicle manufacturers and the contribution wind turbines, both onshore and offshore, make to our renewable energy needs.

Meanwhile Lucas Aerospace, as a company in its own right, no longer exists, parts of it having been sold off, while other parts no longer exist. Like other UK-based manufacturing companies, Lucas Aerospace was a victim of poor, unaccountable management, and a sad lack of successive governments’ industrial strategy.

By Brian Salisbury, former member of Lucas Aerospace Shop Stewards Combine Committee. Taken from http://lucasplan.org.uk/